To Rachel Jackson, October 7, 1814

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, American newspapers occasionally printed the texts of letters to and from Andrew Jackson. In many cases newspaper printings of Jackson letters constitute the only remnants of those letters, the original manuscripts having been lost or destroyed. The circumstances occasioning the publication of Jackson letters in newspapers varied. In the first few decades after Jackson’s death, political controversies frequently motivated recipients and holders of Jackson letters to come forward and publicize them as a way of enlisting Old Hickory’s authority for this or that position. During the Civil War, for example, a handful of letters written by Jackson in the 1830s excoriating South Carolina and disunionism were deployed to criticize the Confederacy and insinuate that Jackson, were he alive, would have been a Unionist. Since the latter part of the nineteenth century and through the twentieth century, however, the discovery of a previously unknown Jackson letter, however found and whatever its topic, was itself a newsworthy event, and Jackson letters printed in newspapers tended to be less substantive and their appearance in print less tied to contemporary disputes.

When the Papers of Andrew Jackson project did its initial search for Jackson documents, it canvassed files of newspapers, but limitations of time and labor necessarily restricted that search to Nashville newspapers and a few nationally prominent titles such as the New York Times. Fortunately, the advent of digital newspaper archives in the first decade of this century made finding Jackson documents in newspapers much easier. Searching for reoccurring tags, such as the distinctive way Jackson closed his letters—“your obedient servant, Andrew Jackson”—allowed the project to locate Jackson letters published in obscure newspapers that never would or could have been searched manually.

The historical importance of many of the Jackson letters found this way surprised and continues to surprise the project’s editors. In 2007, for example, a digital search discovered the following letter from Andrew Jackson to his wife Rachel published in the December 27, 1862, issue of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin in a dispatch via Overland Express by that paper’s St. Louis correspondent. According to the Bulletin‘s correspondent, the letter was obtained by Major John L. Pugh, a Union Army officer from Ohio who was serving in Tennessee. Andrew Jackson Jr., Jackson’s adopted son, allegedly gifted the letter to Pugh during a visit to the Hermitage. What connection, if any, there might have been between Pugh and Jackson Jr. is unclear; that Jr. would have surrendered such a valuable memento to a complete stranger, a Union officer no less, is strange but not impossible.

Short as the letter is, it manages to embody quite dramatically Jackson’s complexity as a historical figure. In the first paragraph Jackson waxes eloquent about the recent burning of the U.S. Capitol by the British and delivers a stirring appeal to the “every man who has a spark of national pride” to rally and “crush the enemies to our country.” In the letter’s second paragraph, however, we learn that, while toiling tirelessly in the fall of 1814 in defense of his country, Jackson also found time to purchase enslaved persons and add to his already sizable slave holdings. Of the eight enslaved persons purchased by Jackson, project editors are able to trace the sale and identity of only three. On September 7, Jackson purchased from Francisco Touard of Pensacola, for the sum of $850, Sampson (c1788–1833), his wife Pleasant (c1781–1847), and their son George (c1810–1830). The bill of sale for that purchase at least did make its way back to the Hermitage, and it resides today in the Library of Congress’s Jackson Papers collection.

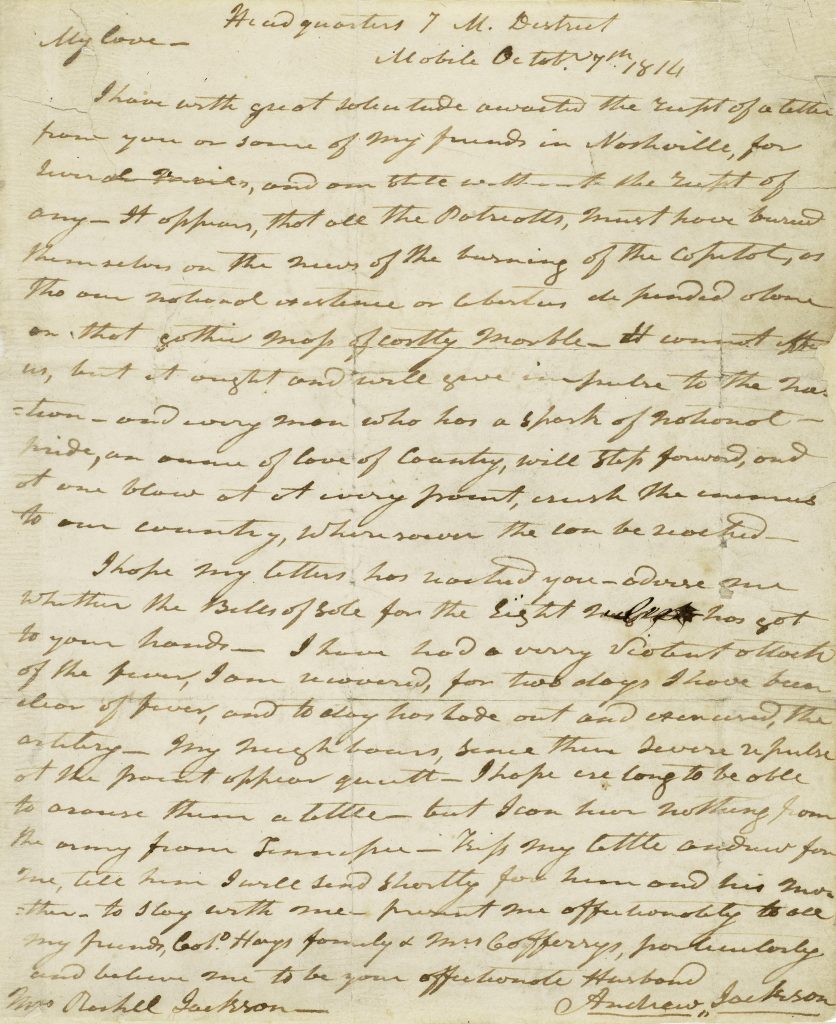

The Bulletin‘s correspondent indicated that Pugh donated his Jackson letter to an organization called the Young Men’s Literary Association of Cincinnati. No such organization or its records existing today, the original manuscript of the letter was assumed lost forever. It was to our great surprise, therefore, that Christie’s in April 2021 auctioned the original manuscript letter, which fetched $27,500. (It was resold by Bonhams Auction house in June 2023, when it went for only $18,000).

The surfacing of the original letter, incidentally, allowed project editors to evaluate the accuracy of the Bulletin’s transcription (which we later learned had first been published weeks earlier by the Bulletin‘s correspondent in the December 6, 1862, Daily Missouri Republican). While over all it provided a faithful rendering, what is immediately noticeable is its correction of several of Jackson’s misspellings (“Patriotts” is changed to “patriots,” “artilery” to “artillery”) and grammatical mistakes (“my letters has reached you” is changed to “my letters have reached you”). Such silent corrections of Jackson’s frequently error-prone writing are not uncommon and occurred more often than not in instances where we have the ability to compare nineteenth-century newspaper printings against original manuscripts. Many newspaper editors, it should be noted, opted to retain Jackson’s original spelling and grammar, and stated explicitly their decision to do so, so as to retain the color and flavor of the original, or in some cases to draw attention to Jackson’s literary deficiencies.

Andrew Jackson to Rachel Jackson

Headquarters 7 M. District

Mobile Octobr. 7th. 1814

My love—

I have with great solicitude awaited the recpt of a letter from you or some of my friends in Nashville, for several mails, and am still without the recpt of any. It appears, that all the Patriotts, must have buried themselves on the news of the burning of the Capitol, as tho our national existence or liberties depended alone on that gothic mass of costly marble. It cannot effe[ct] us, but it ought and will give impulse to the nation—and every man who has a spark of national pride, an ounce of love of Country, will step forward, and at one blow at every point, crush the enemies to our country, wheresoever the can be reached.

I hope my letters has reached you—advise me whether the Bills of sale for the Eight negroes has got to your hands. I have had a verry violent attack of the fever, I am recovered, for two days I have been clear of fever, and to day has rode out and exercised, the artilery. My neighbours, since there severe repulse at the point appear quiett. I hope ere long to be able to arouse them a little—but I can hear nothing from the army from Tennessee. Kiss my little Andrew for me, tell him I will send shortly for him and his mother—to stay with me—present me affectionately to all my friends, Colo. Hays family & Mrs. Cafferrys, particularly and believe me to be your affectionate Husband

Andrew Jackson

ALS, Bonhams, Fine Books and Manuscripts Sale, June 22, 2023, Lot 108. Printed, St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, December 6, 1862.