During his lifetime, Andrew Jackson was frequently dubbed a “Second Washington,” and, indeed, there is much to recommend the comparison. Both George Washington and Jackson were generals-turned-presidents who had saved the country from the British on the battlefield. Other similarities, however, were not so flattering: both were slave owners, had little in the way of formal education, and were known for occasional fits of bad temper.

Throughout both the 1824 and 1828 campaigns as well as during his presidency, Jackson’s supporters juxtaposed the two men for propaganda purposes. Friendly newspapers crowned Jackson “the second Washington and Saviour of his country,” and public events were staged capitalizing on the comparison. In 1824, for example, Jackson was gifted with a pair of Washington’s pistols, and in 1833 he spoke at a cornerstone-laying ceremony for a monument honoring Washington’s mother in Fredericksburg, Va.

In reality, Jackson’s attitude toward Washington was much more complicated than these appropriations suggest. Many people do not realize that Washington and Jackson’s political careers overlapped, and that Jackson, who was a freshman congressman during Washington’s final months as president, once had rather mixed feelings about the “Father of His Country.” Jackson was a Democratic-Republican who, during his tenure in Congress, sided quite consistently with the Jeffersonian opposition and against the supporters of presidents Washington and Adams. On December 15, 1796, Jackson was one of only 12 congressmen who voted against approving a speech thanking Washington for his Farewell Address.

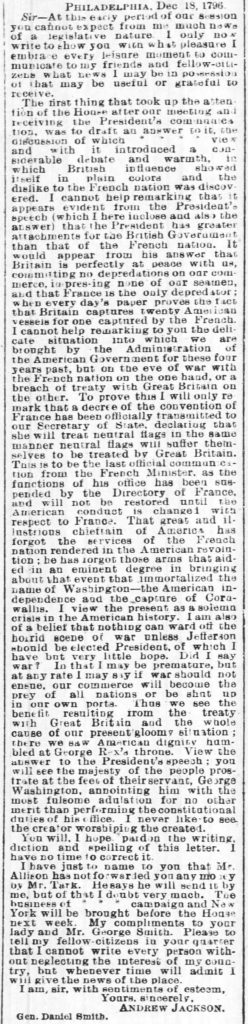

The extent of Jackson’s disillusionment with Washington is revealed in a remarkable letter he wrote three days after that vote. Addressed to Daniel Smith (1748–1818), a family connection and future U.S. senator from Tennessee, Jackson’s letter was until recently thought to be mostly lost to posterity.  The manuscript, which is housed in the Library of Congress’s Jackson Papers collection, is so badly mutilated that only the opening lines and several stray passages survive. A near-full text of the letter, fortunately, was recovered by the Papers of Andrew Jackson in 2008 when it was found printed in an 1879 issue of the New Orleans Daily Picayune. The presence of lacunae in the text there printed (marked on two occasions by asterisks) suggests the manuscript had already suffered deterioration by 1879.

The manuscript, which is housed in the Library of Congress’s Jackson Papers collection, is so badly mutilated that only the opening lines and several stray passages survive. A near-full text of the letter, fortunately, was recovered by the Papers of Andrew Jackson in 2008 when it was found printed in an 1879 issue of the New Orleans Daily Picayune. The presence of lacunae in the text there printed (marked on two occasions by asterisks) suggests the manuscript had already suffered deterioration by 1879.

Andrew Jackson to Daniel Smith

Philadelphia, Dec 18, 1796.

Sir—

At this early period of our session you cannot expect from me much news of a legislative nature. I only now write to show you with what pleasure I embrace every leisure moment to communicate to my friends and fellow-citizens what news I may be in possession of that may be useful or grateful to receive.

The first thing that took up the attention of the House after our meeting and receiving the President’s communication, was to draft an answer to it, the discussion of which * * * * view and with it introduced a considerable debate and warmth, in which British influence showed itself in plain colors and the dislike to the French nation was discovered. I cannot help remarking that it appears evident from the President’s speech (which I here inclose and also the answer) that the President has greater attachments for the British Government than that of the French nation. It would appear from his answer that Britain is perfectly at peace with us, committing no depredations on our commerce, impres[s]ing none of our seamen, and that France is the only depredator; when every day’s paper proves the fact that Britain captures twenty American vessels for one captured by the French. I cannot help remarking to you the delicate situation into which we are brought by the Administration of the American Government for these four years past, but on the eve of war with the French nation on the one hand, or a breach of treaty with Great Britain on the other. To prove this I will only remark that a decree of the convention of France has been officially transmitted to our Secretary of State, declaring that she will treat neutral flags in the same manner neutral flags will suffer themselves to be treated by Great Britain. This is to be the last official communication from the French Minister, as the functions of his office has been suspended by the Directory of France, and will not be restored until the American conduct is changed with respect to France. That great and illustrious chieftain of America has forgot the services of the French nation rendered in the American revolution; he has forgot those arms that aided in an eminent degree in bringing about that event that immortalized the name of Washington—the American independence and the capture of Cornwallis. I view the present as a solemn crisis in the American history. I am also of a belief that nothing can ward off the horrid scene of war unless Jefferson should be elected President, of which I have but very little hope. Did I say war? In that I may be premature, but at any rate I may say if war should not ensue, our commerce will become the prey of all nations or be shut up in our own ports. Thus we see the benefit resulting from the treaty with Great Britain and the whole cause of our present gloomy situation; there we saw American dignity humbled at George Rex’s throne. View the answer to the President’s speech; you will see the majesty of the people prostrate at the feet of their servant, George Washington, annointing him with the most fulsome adulation for no other merit than performing the constitutional duties of his office. I never like to see the creator worshiping the created.

You will, I hope, pardon the writing, diction and spelling of this letter. I have no time to correct it.

I have just to name to you that Mr. Allison has not forwarded you any money by Mr. Tark. He says he will send it by me, but of that I doubt very much. The business of * * * campaign and New York will be brought before the House next week. My compliments to your lady and Mr. George Smith. Please to tell my fellow-citizens in your quarter that I cannot write every person without neglecting the interest of my country, but whenever time will admit I will give the news of the place.

I am, sir, with sentiments of esteem, Yours, sincerely,

Andrew Jackson.